As I was finishing the 2005 best-selling book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcom Gladwell, I was struck by how some of his research and stories made sense of what happened to Notre Dame football over the past five years.

In a nut shell, the book looks into various ways our unconscious mind plays a role in our decision making in everything from spotting fake ancient sculptures, taste-testing soft drinks, creating facial expressions, choosing dating partners and catching criminals.

For a nice concise summary of the book, click here.

Gladwell asserts that we form (in the matter of seconds or sometimes milliseconds) intuitive responses unconsciously, or what he terms “the blink” or “thin-slicing”, and that often times this form of thought is powerfully correct.

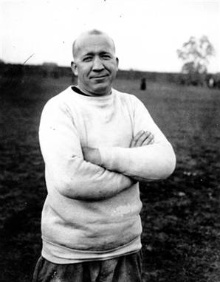

What does this have to do with Notre Dame football? Well, the book itself dives into many different areas of our unconscious mind, both positive and negative, but there were three key arguments that kept setting off alarm bells for a major reason why Charlie Weis failed in South Bend.

Quite simply, Weis and the teams he led onto the field thought too much. They overcomplicated everything from day one, be it through sophisticated game plans, the continuing hiring and firing of coaching and the switching of personnel.

His players never used “the blink” very often, by making use of the powerful ability to make snap decisions in the heat of the moment, because Weis had his players bogged down with too much information. Instead of picking a simple formula for success, Weis led government-like scouting reports that laid too much chance for success on complicated offensive schemes and blitz packages.

A great example in the book came from a story about a man who came up with a simplified medical chart to help the over-crowded Cook Hospital in Chicago treat its chest pain visitors.

The problem beforehand, was that doctors were using too much information, taking too many tests (which often contradicted each other) and many times ended up giving poor diagnoses.

But with the simplified chart, the doctors were ordered to follow its three-step procedure and base the rest of their decision on their gut-feeling as medical professionals.

The result? The hospital diagnosed patients properly over 90 percent of the time with the simplified process, compared to roughly 50 percent before.

If diagnosing heart attacks were like trying to win football games, Charlie Weis would be the doctor too caught up in a mountain of data and test results to bring about victory.

The second example is the story of Paul Van Riper, a heavily decorated retired Marine officer who was brought in by the Pentagon to be part of a 21st Century war game.

Van Riper’s assignment was to be the leader of a rogue nation in the Middle East that would be battling U.S. forces in a multi-million dollar simulated war inside the halls of a cavernous northern Virginia government complex.

The disparity between the two forces before the war could not have been any greater. The Americans (Team Blue) had an overwhelming amount of power in troops, ships, artillery and planes to go with nearly unlimited technology and surveillance. It was expected that Team Blue would win the conflict swiftly and with ease.

However, Van Riper’s Team Red ended up defeating the Blue side almost as quickly as the Blue’s thought they would win the war.

The main reason was that Van Riper was decisive and gave his commanders a lot of power to react to situations in the moment to gain advantages wherever possible. On the other side, Team Blue held long meetings and briefings, poured over enormous amounts of data, acted slowly and found themselves dead in the water in a matter of days of simulated time.

The final example from the book details the outcome of the Battle of Chancellorsville during the American Civil War.

On the Union side there was General Joseph Hooker and over 130,000 troops against the Confederacy’s Robert E. Lee and roughly 60,000 men. Before the battle, the Union held nearly every conceivable advantage including an impressive maneuver to encircle Lee’s army and pin them against the Rappahannock River.

However, the battle was not won by the Union and Lee dealt a serious blow to the Union’s chances of winning the war in one of the greatest victories and upsets in military history.

Why? It was because even with more troops, artillery, spies and information, Hooker became indecisive and was unable to coordinate his army during the heat of the moment. In contrast, Robert E. Lee was boldly decisive and took the initiative with less information and less power to use.

I can’t help but think that Charlie Weis was to Notre Dame what Joseph Hooker was to the Union Army.

In both the war game and Chancellorsville, Team Blue and General Hooker were overly satisfied with their advantages and superiority. Just like Weis, they believed a major “schematic advantage” would win the day.

Often times Weis would lead the Irish on to the field against a weaker opponent only to find himself licking his wounds after a Notre Dame loss. Against teams like Syracuse, UConn and Navy, Weis’ teams had a monopoly of talent, yet they did not win. A schematic advantage was not enough.

The Irish teams from 2005-09 suffered from major “analysis paralysis” that hindered the team’s ability to perform at the highest level. Instead of picking one offense, Weis made his teams learn a multitude of differing packages, often switching game plans in the middle of a contest.

Meanwhile, while opponents were busy making adjustments in real time, Weis continually sought out too much information, consulting his atlas sized play sheet for a different formation to send to the huddle. In effect, Weis was merely guessing his way through games as coach of Notre Dame.

It’s not so much that Weis used such a thick playbook and tried to use his “schematic advantage” to beat teams, but that his entire system of operation was bogged down in paralysis because this “schematic advantage” permeated through every player.

Just think about Harrison Smith looking lost at the line of scrimmage and leaving a receiver wide open for a big play. Does that look like someone who was thinking without thinking? Or did it look like someone too confused by the plethora of coverages to know what he was doing?

If Weis had run a power running game similar to Alabama, concentrated on performing that system to perfection, and then used some of his offensive genius to make big plays, perhaps things would have worked out.

Instead, Notre Dame ran the ball 50 times one game, switched to a pro-style offense the next game, switched to shotgun Texas Tech ball the next, switched to West Coast style the next and everything in between. And the biggest problem was that these moves were made during games and sometimes from series to series.

And most of all, this attention to schematic advantage lessened the influence of crucial qualities which college football players need such as motivation, development and conditioning.

In short, Weis was not a very good leader. In the above examples of the Chicago heart chart, Pentagon war game and the battle of Chancellorsville, each problem was solved by someone with incredible intelligence. While it certainly takes a lot of studying and experience to be able to find solutions to the most difficult of problems, knowledge alone is not enough.

No one can deny that Charlie Weis was a smart man, but he never figured out that you can’t treat players like professionals and that scouting and clever formations alone wouldn’t win football games.

Almost immediately, Notre Dame fans have been struck with how different of an approach Brian Kelly is taking in South Bend.

Because of Kelly’s intelligence and experience, he knows what it takes to succeed. We’ve already heard him speak about how important it is to get players to develop and push themselves, to buy into the system, to learn it through and through and to be able to perform at the highest of levels without even thinking about it. It’s something Kelly calls, “unconscious competence.”

As Kelly said, “You can move them to a level that they can’t get to by themselves. That’s player development. That’s at the core of what I mean, to get people to do things that they normally wouldn’t do on their own. ”

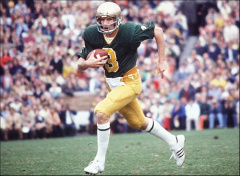

In other words, Kelly wants Notre Dame football players to have “the blink” when it comes time to step on the field. He wants them to have confidence in their abilities as players and build a team that can think without thinking. That’s how you take a bunch of two and three star recruits to an undefeated season in the Big East.

Player development, strength and conditioning and fundamentals are three major areas that Kelly has stressed throughout his entire career and it is obvious that his players have been able think without thinking because of their preparation under this system.

When the entire coaching philosophy trickles down the program from a schematic advantage viewpoint, players cannot be developed very well. Without player development there is no harnessing of the potential of the unconscious mind and the ability to think without thinking is slowly stifled.

And the ironic part of is, the team that stresses schematic advantage usually ends up being out-schemed on the field because its players are not adequately prepared for a team that has confidence to think without thinking.

Do not think I believe that the solution to all of Notre Dame’s problems comes from “the blink” factor. There are too many aspects to coaching and winning football games to break it down to something that simple.

However, it is an interesting topic that showcases how successful people, organizations, company’s and teams can harness the ability to act decisively with the proper training in order to gain an edge on the competition.

In a lot of ways, Charlie Weis’ coaching staff was a lot like the U.S. Government during the Pentagon war games. Weis hired some of the best coordinators and recruiters in the country, just like the government brings together the best talent from different federal agencies.

The problem is, without an effective leader laying down a plan for everyone to follow, the odds of success are severely diminished.

Weis hired two defensive coordinators, each of whom had different coaching philosophies. Corwin Brown thought his way would work best, but John Tenuta believed his would work even better.

This is no different than the CIA or FBI trying to work together when both agencies are working in opposite directions.

The result is major dysfunction and a total lack of comprehension during the most critical times of battle during war and on the football field.

As Gladwell points out in the end of the book, “The key to good decision making is not knowledge. It is understanding.”

Both Weis and Kelly have the knowledge. But so far, Weis has proven he did not understand college football.

So far, Brian Kelly has shown through his coaching hires, speeches and football past, that he is the type of coach who knows how to lead and set a foundation for success.